Scientists seeking to measure wildlife biodiversity in nature reserves are using leeches as a model.

In a new study led by a team of Harvard researchers, DNA samples extracted from leech blood meals were used to map animals living in the Ailaoshan National Nature Reserve in Yunnan, China. The findings suggest blood-sucking worms may be a simpler and cheaper surveillance tool for some biodiversity surveys than existing tools such as camera traps and bioacoustic recorders.

"This study shows how leech-derived DNA can be used to estimate biodiversity, making it a real-world conservation tool," said Chris Baker, a postdoctoral researcher in Naomi Pierce's lab at Harvard University and one of the first members of the study. "author. "We are providing a way to measure biodiversity in wildlife, and specifically a way to directly measure biodiversity."

The study used DNA extracted from more than 30,000 leeches to survey more than 80 vertebrate species, including Amphibians , mammals, birds and squamates. The leeches were collected by rangers over three months in a 260-square-mile nature reserve that stretches nearly 80 miles along a mountain ridge in southern China.

The work, published in Nature Communications, addresses a major practical challenge in measuring animal biodiversity over large spaces. Protected areas are often set aside to protect wildlife communities, but directly monitoring these communities is expensive and time-consuming.

"You can set up automated cameras; you can set up voice recorders; or you can do it manually and have people go out into the field and investigate, but it's hard to do that at scale," Baker said. "These surveys are often limited either by the scale of space they can cover, by the frequency with which they can be done, or by the resolution they can provide. We hope to be able to use environmental DNA as a way to address this problem …rather than having to rely on proxies such as forest cover or ranger budgets.”

Leeches proved to be perfect for the job.

For starters, they are plentiful, at least in tropical environments. They also feed on a variety of animals, from large bears to small mice. Because leeches do not travel but wait, their diets represent a record of which animals passed through the areas where they were found. Worms digest slowly, so scientists at China's Kunming Institute of Zoology, working with Harvard researchers, were still able to obtain the animals' blood from leeches four months after their last feeding.

Researchers look for DNA sequences found only in vertebrates to identify animals. Past research has suggested this is possible, but this is believed to be the first time such an analysis has been carried out on such a large scale.

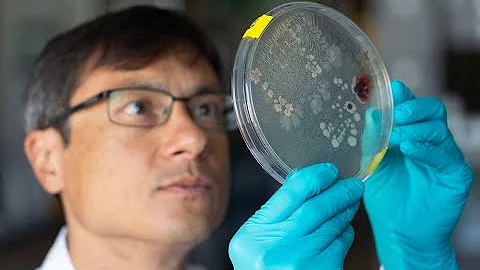

Researchers at Harvard and the Kunming Institute coordinated the collection with approximately 160 volunteer park rangers. The team in China extracted DNA from the samples, arranged for sequencing and investigated which animals the DNA belonged to. Their Harvard colleagues analyzed the animals' locations using a technique called multispecies occupancy modeling, which explains ecological patterns.

The team was able to identify 86 species of vertebrates. Some of them are listed as Near Threatened or Threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. These include Asiatic black bears , tufted deer, rhesus macaques, several species of frogs, and an antelope-like creature called an antelope.

The study also shows that human activities such as agriculture, livestock management and poaching are placing increasing pressure on protected areas. For example, DNA from cattle, sheep and goats was extracted from leeches collected within the reserve, particularly near the edges. This suggests that animals from surrounding farmland are grazing within the reserve and are therefore competing for resources with animals within the habitat or otherwise degrading the habitat. The researchers are optimistic that their findings can serve as a baseline to help track changes in wildlife populations in the Ailao Mountains, and that the method can serve as a strategy to improve wildlife monitoring in leech-rich tropical and subtropical regions.

They also see broader applicability in tracking zoonotic reservoirs, as leech blood meals can also be screened for the viruses they contain. This is particularly important given that the COVID-19 pandemic may have been harbored by animals such as bats and transferred to humans.

"This is a very efficient way to sample large numbers of wildlife, and it's a good way to do it if we think [zoonotic reservoirs] are really worth worrying about and monitoring," said Hessel Professor Pierce of OEB Biology and comparative Zoology Curator of Lepidoptera at the Museum.

This work was supported by a grant from the Harvard Global Institute.

For more biodiversity technology news, please go to Keqi Island

![Introduction: hello, everyone, I am Brother Diao. Today I would like to introduce to you the pet industry’s first column for the global high-quality production and supply chain [Production Capacity Map], which was jointly launched by the Pet Industry Association and the China Pet - DayDayNews](https://cdn.daydaynews.cc/wp-content/themes/begin/img/loading.gif)